26.06.2021 | Author: Soledad Magnone

Para leer en español, cliquea aquí

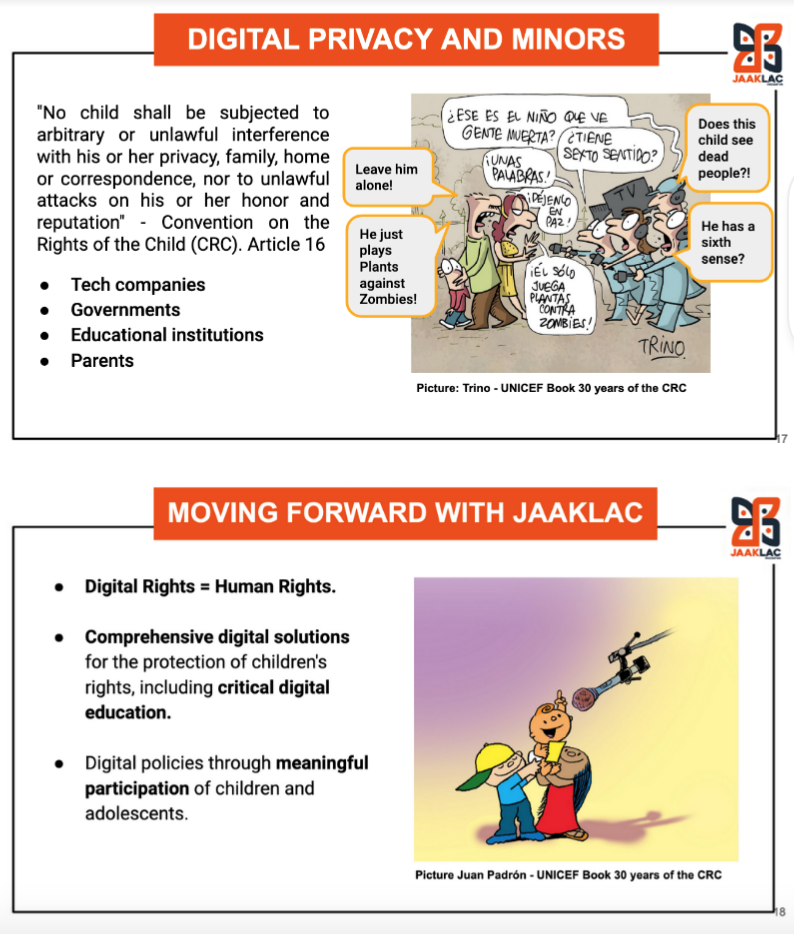

Closing gaps: digital education based on human rights

With this article we want to share the dynamics, materials and reflections of the workshop held on June 8th at the 10th RightsCon, the most relevant conference on human rights in the digital age organised by Access Now. The workshop “Children’s and Adolescents' Privacy and Data Protection Rights: We Do It Together!” is part of a series of critical digital education practices on this topic previously developed at the Mozilla Festival (MozFest). Seeking to contribute to the pressing need to close gaps in digital education, especially on digital privacy issues, JAAKLAC initiative systematises and openly shares resources and lessons learned (Magnone, 2021).

It is important to present that we understand “digital education” as a concept that encompasses two dimensions of teaching and learning: (a) using digital technologies and (b) understanding how they work (Bayne and Ross, 2011). At JAAKLAC we focus on the second dimension through research, educational activities and awareness-raising campaigns. These are human rights-based to inform policies, programmes and practices that are comprehensive and oriented towards the best interests of individuals, societies and democracies.

(1) Discussing privacy policies and personal data protection.

The workshop was co-facilitated by Azeneth Garcia (Causas Digitales), Eliany Guardado (Red Concausa), David Aragort (Redes Ayuda / Causas Digitales) and Soledad Magnone (JAAKLAC initiative). We began the session by posing questions such as “what does privacy mean and how important is it for you? As one of the participants answered, “it is a right that allows us to decide with whom, how and when to share my personal information or my privacy”. It was raised in the group that its relevance can vary depending on cultures, people and their moments in life. For example, it is more valued in adolescence than in childhood and that in Latin America we tend to be more effusive when sharing personal information, which may explain why privacy is not on the agenda in the same way as it is in Europe.

Currently, the focus of human rights in the digital age is broadening. It has shifted from prioritising access to the internet to giving greater centrality to digital privacy. This is due to the growing phenomenon of “datafication” of individuals, resulting from their intense interaction with digital technologies and the push for digital transformation in organisations in sectors such as social security, employment, education, health, among others. At the same time, personal information became of significant market value, leading to the popularisation of the concept of “data capitalism” (Beer, 2018) or “surveillance capitalism” (Zuboff, 2019). This Apple video illustrates the sense of loss of privacy that more and more people are experiencing, and which motivated the development of its new iPhone functionality to control data shared with apps.

(2) Representing different groups in a role-play based on a real scenario.

In order to deepen and discuss a real case regarding privacy and data protection of minors, we chose the controversial application “Google Family Link”. For this purpose, we presented the following activity: “Family Link allows parents to supervise children and adolescents' mobile phones, controlling screen time and the type of applications used, among other things. The case of Family Link resonates with the famous episode “Arkangel” of the dystopian sci-fi series “Black Mirror”, in which a mother implants a microchip in her daughter to monitor her. Family Link highlighted the broad disagreements between minors and adults over such a solution: the app has very low ratings in its “children and teenagers” version compared to the “parents””. For the role-play we pose the fictitious scenario in which Google calls for a consultation to improve its app to: (a) children and adolescents, (b) parents and (c) child rights agencies.

(3) Designing digital solutions for the protection and participation of children and young people.

Our role play was dominated by the voices of young people and digital rights and child rights activists. In general, there was a strong consensus among participants that there should not be an app with such features. Participants pointed out that there are already functionalities on mobile phones such as “share your location” that can help, for example, to locate lost people. As a solution, it was underlined that the most important thing is to “generate agreements and trust (it is more difficult but it can start from there)" between minors and adults. Also, in the case of redesigning the application, children and adolescents should have the possibility of activating or deactivating functions by their own decision or in case they feel at risk.

From the point of view of agencies for the rights of minors, it was highlighted that awareness-raising campaigns on digital rights should be carried out, “addressing them from the school curriculum in digital citizenship classes” and including digital security issues. Strategies should also be implemented so that “the participation of young people does not pass through a filter of adult interpretation”. In this sense, the workshop recommended the creation of spaces for the co-design of digital solutions and that governments should attend to local needs, not the interests of international tech companies. The handling of data collected from minors by Family Link was also questioned, in light of the fact that Google has been involved in abuses on several occasions, for example, with its educational services (Gebhart, 2017).

(4) Sharing expertise and materials to promote critical digital education.

Like adults, children under the age of 18 are subject to datafication practices. Their data is used for surveillance and behavioural prediction by governments, the technology sector, schools, parents (Barassi, 2020; Hope, 2018; Lupton and Williamson, 2017; UN GA, 2019). Privacy is key to autonomy, human dignity and the realisation of a wide range of fundamental rights. As one workshop participant noted, “privacy is a birth right, not a coming of age right”. It is particularly important for children, who do not have the capacity to understand the implications of the challenges of the digital age and which physical, cognitive and emotional vulnerabilities are amplified. It is therefore imperative to reverse this context through solutions that balance the protection and participation of minors (Livingstone, Carr and Byrne, 2015).

In order to manifest changes guided by approaches balancing rights and participation, JAAKLAC openly share the experience and lessons learned at RightsCon. The dynamic was co-created with youth to facilitate the connection between generations and was positively valued by its participants. To amplify our community we invite you to:

-

Do activities in digital education inspired by our workshop (presentation here) and to share your ideas.

-

Join Causas Digitales, a group of young Latin Americans activating rights and inspiring digital innovation. Receive news and participate in activities by filling out our form.

-

Learn about the UNICEF manifesto for better governance of children’s data.

🚀 Inspiring broader communities 🚀

References

Apple (2021, 20th May) Privacy on iPhone | Tracked | Apple. Youtube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8w4qPUSG17Y.

Barassi V (2020) Datafied Citizens in the Age of Coerced Digital Participation. New media & society, 22(9) 1545–1560.

BBC News Mundo (2018, 20th September) Family Link, la polémica app de Google que permite a los padres controlar el celular de sus hijos minuto a minuto. BBC online. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-45587373.

Beer D (2018) The data gaze: Capitalism, power and perception. Sage.

Gebhart (2017, 13th April) Spying on Students: School-Issued Devices and Student Privacy. Electronic Frontier Foundation. Available at: https://www.eff.org/wp/school-issued-devices-and-student-privacy

Hope A (2018) Unsocial Media: School Surveillance of Student Internet Use. In: Deakin J, Taylor E and Kupchik A (eds) The Palgrave International Handbook of School Discipline, Surveillance, and Social Control. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 425-444.

Livingstone S, Carr J and Byrne J (2015) One in Three: The Task for Global Internet Governance in Addressing Children’s Rights. Report, Centre for International Governance Innovation and Chatham House, London, November.

Lupton D and Williamson Ben (2017) The datafied child: The dataveillance of children and implications for their rights. New media and Society 19(5): 780–794.

UN GA (2019) Report of the Special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. Report for the Human Rights Council 74th Session A/74/48037. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Poverty/A_74_48037_AdvanceUneditedVersion.docx.

Zuboff S (2019) The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. New York: PublicAffairs.